Sources of inspiration

|

In the year that I was writing this journal I was searching for ways to live with a persistent and baffling nerve pain that had worsened following surgery. As well I was struggling with the accompanying emotional pains that accumulate when a person is in crisis. In the beginning I was alone in my home and confined to bed inhabiting the true meaning of invalid. I felt very low and extended trying to ride the huge waves of pain. My life as a writer, teacher and biographer had been put on hold and I felt I was losing my identity. In desperation I resorted to the technique I have always used to claw my way out of difficulty. I went looking for answers in books and online, casting my net wide and examining the writings of authors, artists and thinkers whose experiences dealing with pain and difficulty offered encouragement. During my search I typed ‘pain journal’ into Google and found a lone voice asking, ‘Is anyone out there keeping a journal of pain and if so what are they putting in it?’ That was when I committed to writing and publishing my journal. I hoped that by writing my personal story and being honest about all the things that were perplexing me I might help others also afflicted with ongoing suffering. You will need to read my journal for the full account of what emerged in those pages but below I offer a selection of the books, ideas, people, programmes and techniques that helped me through that year and continue helping me to this day.

: |

|

Her Life’s Work: Conversations with Five New Zealand Women by Deborah Shepard

Auckland University Press, Auckland, 2009 I began with my own book, Her Life’s Work, a series of conversations with five New Zealand artists, writers and thinkers – painter Jacqueline Fahey, educator Merimeri Penfold, anthropologist Anne Salmond, film director Gaylene Preston, and writer Margaret Mahy. These discussions were recorded over three years from 2006 to 2009, and then transcribed, edited and refined in collaboration with each of the women participants. In that book I had posed questions on resilience and endurance, grief and loss, on ageing and physical deterioration and confronting mortality. I wanted to know how these five bold women had negotiated difficulty and how they stayed strong in the midst of adversity. Most important I wanted to know how they maintained their creativity. I had no idea then just how relevant and important their wise counsel would become. In my time of need I found myself latching on to what they had to offer attending again to their words, imagining their beautiful faces, listening for their voices. I derived immense comfort as I lay in bed from visualising them talking to me. |

|

Virtues Reflection Cards by Linda Kavelin-Popov

Virtues Project International Association, 2006 www.virtuesproject.com Early on in my recovery, on a day when I was struggling with the acute post-surgical pain there was a phone conversation with my mother, who has multiple sclerosis and lives in hospital level care in a retirement village. We were talking to each other from our beds, me in Auckland, my mother in Christchurch. My mother suggested we pick a Virtues card and together examine the quality needed to help us through. My mother is a follower of the Human Virtues programme, having trained with the Canadian founder of the programme, Linda Kavelin-Popov. She used the principles in her teaching and even today she continues to facilitate a Virtues circle from her wheelchair in the hospital that has become her home. My response was to say I couldn’t possibly find the capacity for endurance, fortitude or forbearance — the pain was too hard. Then my mother said, ‘How about "grace’"?' Her suggestion was unexpected. I found it intriguing and gentle. That virtue remained with me as something worth striving for no matter what the circumstances. Still I try to think, move and act with grace. |

|

The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating by Elisabeth Tova Bailey

Alongquin Books, New York, 2011 The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating is a memoir about the author Elisabeth Tova Bailey’s long-term struggle with chronic fatigue syndrome. Her illness was so severe it confined her to bed for two decades in a white room, in a house overlooking salt marshes in the beautiful nature corridor of Maine in New England, North America. She explained that from her bed she could not see out the window and so she lay there imagining the view of the marshes and of her garden down below and derived comfort from the thoughts. And then one day, a friend visited with a pot of purple field violets plucked from a nearby forest. Nestling in the foliage was a snail. ‘What will I do with a snail in a pot?’ she wondered. Gradually she grew interested in the activities of her nocturnal companion that kept her company on the nights when she was unable to sleep. Her book, beautifully written, combines her observations of this little creature, that soon had a home in a terrarium of plants on the table beside her bed, with a wonderfully informative natural history commentary on the humble snail. |

|

The Body Broken: A Memoir by Lynne Greenberg

Random House, New York, 2009 Most of the autobiographical literature on pain is written in retrospect when the nightmare is over and not when the sufferer is ploughing through the middle of it. Eventually I found a book written by an author who, like me, continues to live with chronic neuropathic pain. This author is a New York academic and teacher of seventeenth-century British poetry. Her appreciation of language and lyricism influence her beautiful, eloquent writing. At one point her pain was so bad she was admitted as an in-patient to a hospital pain department where she embarked on a gruelling pain management programme. The aspect of her story that touched me was how poetry helped her. She wrote that she didn’t find peace through the relaxation and meditation sessions that were a regular component of the programme. Instead she remembered a seventeenth-century sonnet by Milton, something he had written to help himself through his own suffering, and began whispering it to herself finding comfort in the recitation of the familiar and long-loved poem. Finding a method that was appropriate and personal to this author encouraged me to think laterally and find my own soothing techniques. |

|

How to be Sick: A Buddhist-Inspired Guide for the Chronically Ill and Their Caregivers by Toni Bernhard

Wisdom Publications, Sommerville, Massachusetts, 2010 It is a human impulse to want things to go well and to expect to be in control. We should be able to fix things when they go wrong. But pain and ill health, loss and grief are a reminder of our vulnerability. This is what makes us human. In the midst of my confusion I came upon a North American law professor Toni Bernhard and her Buddhist-inspired book How to be Sick. This author lives with an autoimmune disorder and like the snail woman is also confined to bed. She says that her book was written over nine years from her bed. I don’t keep many pain books in my bedroom because I’ve found they can have an oppressive effect, however Toni Bernhard’s book sits on the shelf of my bedside cabinet like a totem radiating sound counsel and compassion. This is the book I reach for when I am deeply troubled. The concept I find most helpful is that of equanimity, a core concept of Buddhist philosophy where people learn how to accept difficulty and roll with it rather than trying to fight it. Buddhism teaches us to be non-reactive and equanimity allows me to be lightly curious. Given that the pain is telling me to slow down, to replace the ‘doing’ mode with the ‘being’ mode, what then might I do with my time? Perhaps I can grow to like a quieter existence? I can spend more time nature-watching, noticing the birds and their daily patterns, the flowers in my garden and their changing colours, the sunlight on leaves, on water, the feel of the air on my skin. In this quieter existence I have also discovered that I like knitting very much. I like to knit in the sun in my lounge. I like to knit and think and look out the window and watch a cloud float silently by like a big fantastical ship rolling over a sea of blue silk. |

|

Living Well with Pain & Illness: The Mindful Way to Free Yourself from Suffering by Vidyamala Burch

Piatkus Books, London, 2008 I was drawn instantly to the title of this book. I found the idea of living well alongside pain both novel and surprising. Was this actually possible? Until I read this book I hadn’t known I had a choice. Vidyamala Burch was issuing a challenge with a phrase that pulsed in bright lights: ‘You can choose to lead an awful life with pain, or a good life with pain.’ I was also drawn to the book because it was elegantly written. I am not an enthusiastic reader of self-help manuals and textbooks with their prosaic and prescriptive tone. I prefer to acquire knowledge and insight through reading about the personal and deep experiences of another human being who knows experientially what pain feels like. I like to hear from people who can write with passion and insight and in a holistic way about the reality of living with an unlikeable pain. Vidyamala also unpicks the layers of suffering associated with pain. As well as the physical sensation of pain there is another important dimension. There is the individual’s emotional response, the grief we feel over the loss of good health and the depressive and helpless thoughts that loop and shout, ‘This is unbearable. I can’t live with this level of pain. What if I have it forever? I can’t go on.’ When I accepted that I couldn’t change the physical pain but that I could take charge of my thoughts around the pain, I began to experience a sense of liberation. Working through my defeating thought patterns I found it was possible to reach a place of acceptance where I no longer attach an emotion to my pain. This means that I refuse to enter into any kind of conversation with the pain. The pain ‘just is', a noise, an inconvenience but not a catastrophe. It needn’t limit my life. This shift in thinking did not occur overnight. It required input from a pain psychologist who slowly, over many months, taught me how to manage my thoughts around the pain. It also involved a sustained effort on my part, challenging my assumptions until eventually one day I felt different. I was no longer oppressed. Now I found that many of the activities that had formerly been dismissed as too difficult in the midst of pain seemed possible. |

|

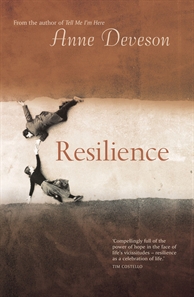

Resilience by Anne Deveson

Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 2003 Resilience is by a Sydney author, broadcaster and film-maker who has made a study of the conditions that promote and sustain resilience and strength of spirit. Her book combines a research element, surveying medical studies on resilience with her own personal experience and sorrow following the death of her son and later of her partner. She has written an earlier book, Tell Me I’m Here, about her son who developed schizophrenia and died of a drug overdose. Resilience was the book that followed the sudden death of her partner. Anne Deveson believes that every human being has an innate survival mechanism and that resilience does not have to be learned, it just needs to be activated. How might it be activated? She believes that having a sense of belonging to family and extended family or to a community can help counteract the isolation and misery that accompanies misfortune and ill health. She also writes about the importance of having mentors who demonstrate ways of being strong. Her book, read soon after the surgery got me thinking about the people in my life who model resilience. I spent many hours in my bed remembering their particular qualities, identifying the mix of courage and pragmatism. I still think about mentors to this day and am ever alert to examples of resilience in others. What I’ve noticed is that those individuals who have an ability to roll out from under a knock and who act swiftly to resume familiar rhythms and routines — work, hobbies and friendships — all the things that provide a sense of security and reassurance and most vitally a feeling of pleasure, these people seem to fare better in adversity. |

|

The Auckland Regional Pain Service

I wasn’t aware until many months following surgery, when my doctor raised the idea, that here, in my own city, at Greenlane Clinical Centre there is a pain department offering an intensive three-week programme in pain management. There may well be a facility like this in your city. The Auckland Regional Pain Service was established in the 1980s by the anaesthetists, Dr Bob Boas and Dr Vasu Hatangdi and subsequently evolved over many years of research and refinement, under the directorship of Dr Bob Large, into a world-class unit providing an holistic approach to pain. The programme contains the following mix of components: gym exercise, lectures about the nature of pain and brain function, cognitive therapy sessions on how to catch and manage distressing emotional responses to physical suffering and quieter activities such as, meditation, relaxation, visualisation and hypnosis to dampen brain activity and ease pain. Initially the days seemed long and I worried about the exercises causing more trouble. But very quickly I felt safe. The physios would never push a person beyond the pain barrier. They reason that staying fit is essential for maintaining body strength and it is preferable to be fit in pain as opposed to unfit. I loved the visualisation exercises especially. I felt like a child again with paints and paper when the art therapist arrived and offered yet another therapeutic modality for helping a person live with pain. This is a very positive hospital programme and an important resource for pain sufferers. Meeting other pain sufferers who really know what it is like to live with constant pain was affirming too. In our own tearoom, and over food and drink, we shared experiences and insights and there was laughter and tears too. As well I met someone there who has become a very dear friend and whose companionship and deep understanding I continue to enjoy today. |

|

Manage Your Pain: Practical and Positive Ways of Adapting to Chronic Pain by Dr Michael Nicholas and Dr Allan Molloy, Lois Tonkin and Lee Beeston

ABC Books, Sydney, 2001, revised edition, Souvenir Press, 2011 I found the opening message of this book confronting because it began with the stark statement that there is no cure for chronic pain. I persevered with the book, however, because I sensed it was probably good for me. It offered a practical and pragmatic guide to managing pain. Written by the experts who facilitate an intensive programme in pain management at the Royal North Shore Hospital, Sydney, something similar to the programme at Greenlane Hospital in Auckland, it has chapters on sleep and coping with flare-ups and setbacks. There are tips on planning realistic schedules and pacing, on ways to protect health, on the benefits of relaxation, on managing pain and work, on realising dreams and problem solving. |

Keeping a Journal

|

Journal of a Solitude by May Sarton

W.W. Norton & Company Ltd, New York, 1973 When my friend gave me the gift of a journal and told me to ‘write my way through’, I wasn’t sure what would emerge. I had never written a journal before. I’d scrawled things on scraps of paper in the middle of the night when I couldn’t sleep, pouring out my deepest, darkest, most tortured thoughts and then with them out on the page, no longer so alarming, I had fallen asleep. For my research projects I had written letters to myself asking questions about my discoveries and where I was heading, what more did I need to read, research, verify, what was worrying me and the steps towards resolving issues, but never before had I explored the personal, nor committed to a regular routine. Turning my attention and focus to the world in close up on my doorstep and recording my intimate feelings on the page for a possible reading audience was a new sensation. When I am entering new territory I go to the experts for guidance and so I went to the maestro of the journal form, May Sarton (1912–1995) and reread her very first and great journal, Journal of a Solitude (1977). Long after this book was published, May Sarton said to her interviewer Karen Saum in the Paris Review that she wrote the journal to help herself through a depression. She was living alone by that time in Nelson New Hampshire separated from Judy Matlock, her partner of thirteen years. What I treasure most about May Sarton’s writing is her willingness to invite the reader into her life and to see inside her personal experience. I admire how she balances passages of writing about her inner thoughts and feelings with observations of the domestic and of nature. She writes about the beauty of the plants in her garden, of daffodils glowing in white light in an old Dutch blue-and-white drug jar on a table in her living room. She writes about her own creative journey, about self-doubt and the trials of the writing life, about the knockback of a negative review as well as the highlights when a letter arrives from a reader who says she found her writing comforting. She notes the books that interest her, she offers portrait studies of significant friends, she writes about loss and love and ageing, about what it is to be human. May Sarton said at one time she didn’t rate her journals as highly as her poetry and novels and was mystified by the attention they received. Today it is the journals and memoirs that continue to speak to readers long after her passing in 1995. Thankfully for her fans the author left us with a significant body of work. There are eight journals, five autobiographies and a book on writing to further satisfy interest. |

|

Journal of Katherine Mansfield edited by John Middleton Murry

Constable & Co. Ltd, London, 1927 I t was in my final year at secondary school that I was introduced to the short stories of Katherine Mansfield. Up until that moment the texts in the English syllabus had implied that great literature existed far away in the Northern Hemisphere, not in our own land. But now we were discovering a writer with a remarkable talent, someone writing with acute sensitivity and beauty about places we knew. On graduation my grandmother gave me the big volume of The Complete Stories of Katherine Mansfield and I hugged them to my chest and read them in every available moment in a broken-up day while working as kitchen hand in a city hospital awaiting the start of university. Katherine Mansfield wrote a journal as well and it was to this work that I returned when pain overwhelmed me. There is a pattern here. I reach for the books that echo what I am feeling at a given time and devour their wisdoms. Reading in this way I find I am more receptive to what a book has to offer. Katherine Mansfield lived with debilitating ill health caused by consumption and she died of the ravages of tuberculosis and a heart condition in 1923, in France when she was only 34. In her journal she wrote bravely and deeply about human suffering. This in my opinion is one of the great advantages of the journal form, that it can be used to explore distress. In the pages of a journal a writer can name and explore emotions and then feeling lighter can move forward with more hope. That is why I advocate for the practice of journalling. |

The value of distraction or finding activities that ease the experience of pain

From the pain psychologist I learned about the value of distraction as a method for managing pain. The trick is to become so engrossed in a distracting task or activity that you no longer notice the pain. It recedes, blessedly, into the background. I also learned from this wise man that there are many forms of distraction and a hierarchy as well. Conversation and the laughter that often surfaces when socialising sits at the top of the register. Lying in bed, alone, feeling your pain is at the bottom. Once again the sources of relief will be particular to you and your style. These are mine.

Reading, memorising and reciting poetry requires focus and application, as does learning to play a new piece of music, writing in a journal, or working on memoir. All of these modalities help me. At school and university, I memorised set poems and they are with me still, brought out and recited in times of trouble, or delight to increase the pleasure and also when I go to the landscapes and locations the poets have written about. Poems recited in this way deepen my experience of living.

From the pain psychologist I learned about the value of distraction as a method for managing pain. The trick is to become so engrossed in a distracting task or activity that you no longer notice the pain. It recedes, blessedly, into the background. I also learned from this wise man that there are many forms of distraction and a hierarchy as well. Conversation and the laughter that often surfaces when socialising sits at the top of the register. Lying in bed, alone, feeling your pain is at the bottom. Once again the sources of relief will be particular to you and your style. These are mine.

Reading, memorising and reciting poetry requires focus and application, as does learning to play a new piece of music, writing in a journal, or working on memoir. All of these modalities help me. At school and university, I memorised set poems and they are with me still, brought out and recited in times of trouble, or delight to increase the pleasure and also when I go to the landscapes and locations the poets have written about. Poems recited in this way deepen my experience of living.

Music

I like to play the piano but since pain I have had to limit my time at the keyboard. Instead I listen to my favourite performers when I am writing, or cooking, and especially in the car as it helps take my mind off the back pain. The pain psychologist suggested soothing music. I enjoy Keith Jarrett, his Koln Concert and Paris Concert because they have classical origins mixed with the romantic and passionate sounds of jazz. I like the lyricism of Scandinavian jazz artists like Lars Danielsson and also Ulf Wakenius and his Forever New album for the same reason. In 1999 I went to the Beara Peninsula in Ireland to record the oral history of documentary director Deirdre McCartin for my book Reframing Women: A History of New Zealand Film. At the end of the two-day interview she gave me a cassette tape of A Woman’s Heart with the Irish folk singers Mary Black, Dolores Keane, Eleanor McEvoy, Frances Black. We played that tape on our car journey through Ireland. So now when I listen to their voices, I am transported back to Ireland in the spring of 1993, the lush green of the hedgerows and the bright and paler pinks of wild roses, the tunnels of elders and beech and the green light shining through their lacy canopies, the narrow, winding roads, the saints in grottos upon the roadside verge. Music has that capacity to trigger memories from the deep and transport you back to a place and time when you were truly happy. Sometimes, though, I crave high-octane music to give me a blast and take me out of myself. Then I go to the pumping energy of singers like Glen Hansard and The Frames.

I like to play the piano but since pain I have had to limit my time at the keyboard. Instead I listen to my favourite performers when I am writing, or cooking, and especially in the car as it helps take my mind off the back pain. The pain psychologist suggested soothing music. I enjoy Keith Jarrett, his Koln Concert and Paris Concert because they have classical origins mixed with the romantic and passionate sounds of jazz. I like the lyricism of Scandinavian jazz artists like Lars Danielsson and also Ulf Wakenius and his Forever New album for the same reason. In 1999 I went to the Beara Peninsula in Ireland to record the oral history of documentary director Deirdre McCartin for my book Reframing Women: A History of New Zealand Film. At the end of the two-day interview she gave me a cassette tape of A Woman’s Heart with the Irish folk singers Mary Black, Dolores Keane, Eleanor McEvoy, Frances Black. We played that tape on our car journey through Ireland. So now when I listen to their voices, I am transported back to Ireland in the spring of 1993, the lush green of the hedgerows and the bright and paler pinks of wild roses, the tunnels of elders and beech and the green light shining through their lacy canopies, the narrow, winding roads, the saints in grottos upon the roadside verge. Music has that capacity to trigger memories from the deep and transport you back to a place and time when you were truly happy. Sometimes, though, I crave high-octane music to give me a blast and take me out of myself. Then I go to the pumping energy of singers like Glen Hansard and The Frames.

Friendship

Friendship in pain, it really helps. We, all of us, need someone who understands our plight, a sister, or a brother in solidarity with whom we can communicate our doubts and sometimes despair. We need someone who doesn’t have expectations and who understands when we have to cancel a meeting and there is no judgement, only love and acceptance. That friend who genuinely cares and delights in your happiness is the one you need to accompany you.

If I was to sum up my message then it is this. You need never feel alone, or that your problems are insurmountable. There is help and solace out there in abundance; it’s just a matter of looking, asking, reaching out and being receptive. It is about giving yourself to life.